Egyptian art had a quality that most art doesn't: it was designed to DO something.

Ask people what is their biggest attraction towards ancient Egypt and a sizeable number will say 'the art'.

Egyptian art is recognisable at a glance and often carries a seemingly serene beauty that we appreciate and value thousands of years after it was made.

However, beautiful as it is, much of this art was meant to be sealed in a tomb and never seen again. Egyptian tombs were like secret art galleries that spoke only to an elite group of visitors – the gods.

If certain formulas were included and the right gods appealed to, all Egyptians, from the wealthy to the poor, could look forward to the gods' protection in successfully navigating the dangerous Underworld through to the blessed, eternal afterlife.

In a sense, Egyptian art was purely functional; tomb reliefs and paintings were meant to be spend eternity serving the deceased.

Tombs often displayed colourful scenes of daily life, which carried messages of power, such as overseeing the efforts of craftsmen or farmers; leisure, such as hunting in the marshes or enjoying music; and abundance, such as scenes of harvesting bountiful crops or banquet tables groaning with food. These scenes provided certainty of a healthy and wealthy afterlife.

The finest Egyptian art that catches our eye today is actually a message to the gods about the deceased's wealth and power: they have the means to commission such beauty in this life, and they want to carry that wealth and status into the next.

However you didn't need to be well off to make it to the afterlife. Museum basements are often packed with objects of less quality made for people of lower status. Despite being less appealing form an artistic sense, they served exactly the same function for their owners and provided the same effectiveness as those made for the royal and fabulously rich.

Because 'art' was really created for religious or royal propaganda purposes, the Egyptians didn't really have a word for 'artist'. Instead, artists were thought of more as artisans or craftsman. This isn't to say there weren't valued like the great artists are today; the elaborate tombs these artisans left behind are testament to the high regard in which they were held - and how much they were paid for their services.

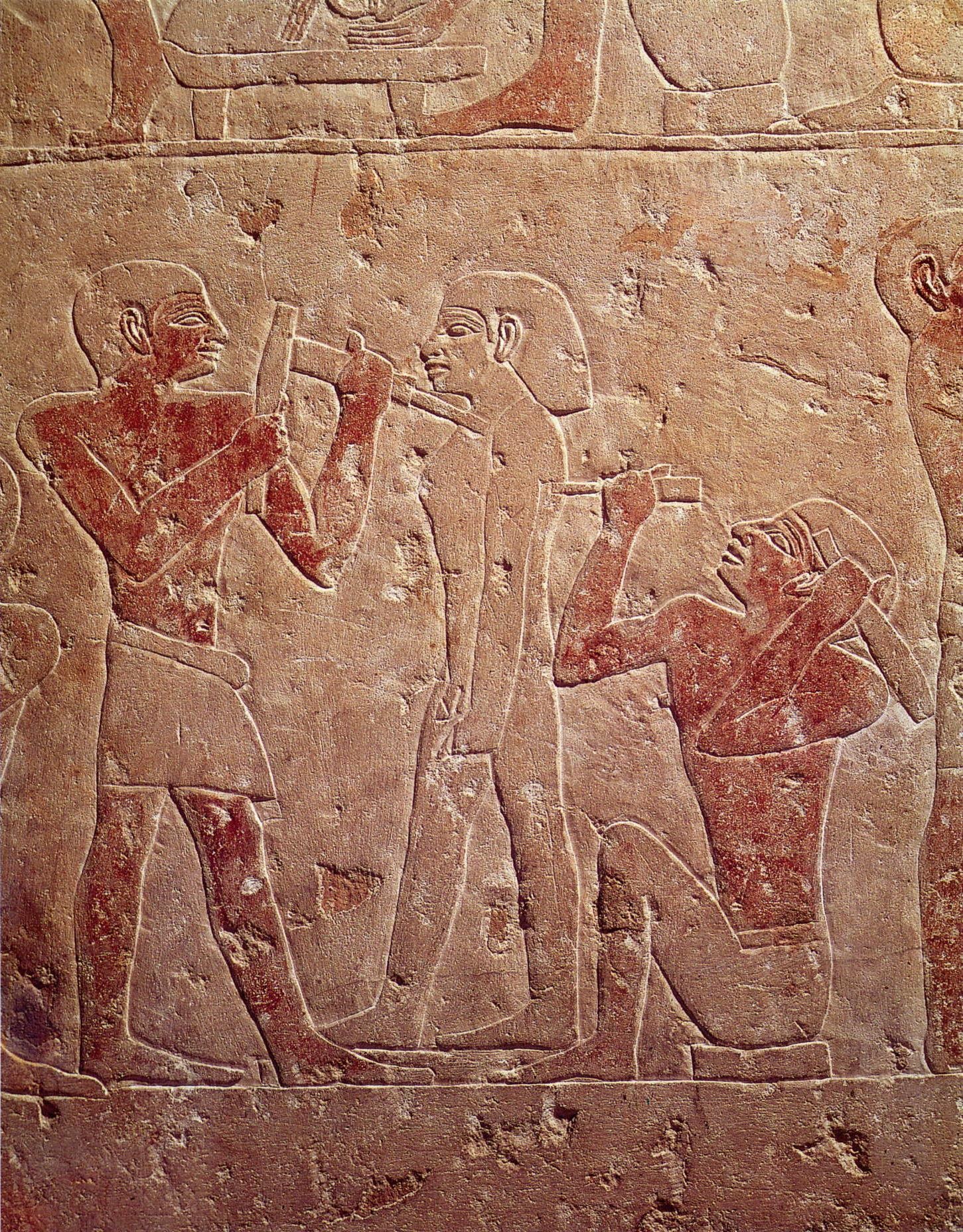

This particular scene comes from the mastaba of Kaemrehu at Saqqara, who was a high priest of the Pyramid of Fifth Dynasty King Niuserre at Abusir, ca. 2,440 B.C.

Here we see two sculptors are working on a standing statue of the deceased. Tomb statues like this one provided a place for the deceased's 'ka' or 'spirit' to manifest and receive the benefits of ritual actions, such as food offerings to prevent the deceased getting hungry in the afterlife. They were often placed in tomb chapels which could be visited by the deceased's family.

The relief, discovered by Auguste Mariette in the 19th century, is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.